How bacteria domesticate foreign DNA

12 Feb 2026

A new study by researchers at LMU shows how bacteria navigate the chaos of acquiring foreign genetic material – turning molecular accidents into evolutionary opportunities.

12 Feb 2026

A new study by researchers at LMU shows how bacteria navigate the chaos of acquiring foreign genetic material – turning molecular accidents into evolutionary opportunities.

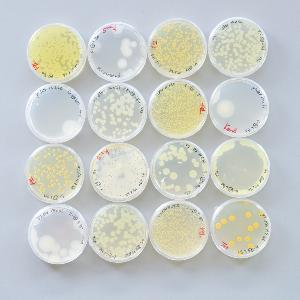

© Carolin Bleese

Horizontal gene transfer – the process by which bacteria swap genetic material directly with their neighbors rather than inheriting it from their parents – allows microbes to rapidly acquire new traits. However, this evolutionary shortcut is a double-edged sword. A new study by researchers at LMU Munich, which has appeared in BMC Biology, reveals that foreign genes can disrupt a host’s existing cellular machinery through “molecular accidents.” Crucially, however, these very accidents can also serve as a catalyst for evolutionary innovation.

Navigating molecular domestication

The study was led by Dr. Tess Brewer, an independent researcher supported by a Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) grant, within the laboratory of

PD Dr. Jürgen Lassak at LMU’s Faculty of Biology. Brewer’s research focuses on the ‘domestication’ phase of evolution – the critical window after a foreign gene enters a new cell but before it is fully integrated. Even after a gene is successfully accepted, its product, that is, the proteins for which it codes, must operate harmoniously with the cell’s existing tools. The work provides a rare experimental glimpse into this immediate aftermath of gene transfer.

The research team focused on protein biosynthesis – the production line within the cell where proteins are generated from genetic information. This is a fundamental process that is highly conserved across all forms of life. While the basic assembly line is shared, the specialized tools that keep it running can differ markedly between bacterial species. One such tool, elongation factor P (EF-P), fits into a narrow pocket of the ribosome, much like a key fitting into a lock. In some bacteria, this key must be lengthened by a specific modification to engage properly, whereas in others it functions without alteration.

From disturbance to innovation

The researchers asked what happens when a bacterium acquires a foreign enzyme that introduces this modification. They found that the enzyme can sometimes act on the host’s own EF-P, producing a key that no longer fits cleanly into the ribosomal lock. This molecular mishap can jam the system, blocking EF-P function and revealing the immediate risk of taking up foreign DNA.

Yet the study also uncovered an unexpected opportunity: Some EF-P proteins are remarkably tolerant and continue to function even with a mismatched modification. This tolerance allows the accident to persist without harming the cell, giving evolution time to refine the mistake. Over time, what began as a misplaced modification can be reshaped into a beneficial new adaptation.

A new dimension of adaptation

The study highlights that the horizontal transfer of genetic material produces a complex balance of interference and opportunity. In some lineages, a period of initial conflict is followed by adaptation, where the ‘invading’ gene transforms from a disruptor into a valuable tool. “Our findings add a rich new dimension to our understanding of how bacteria adapt and innovate,” says Tess Brewer. “What starts as a molecular mismatch can eventually lead to the development of entirely new cellular systems,” adds Jürgen Lassak. For the researchers, the collaboration between Brewer and the Lassak lab exemplifies how independent research integrates into LMU’s scientific framework to answer fundamental questions about the resilience and creativity of life.

Tess Brewer et al.: Horizontal transfer of post-translational modifiers brings evolutionary opportunities and challenges to a conserved translation factor. BMC Biology 2026